"So it goes."

Ella Mc's book blog. Brand new 2018 - Only books read after 1st January 2018

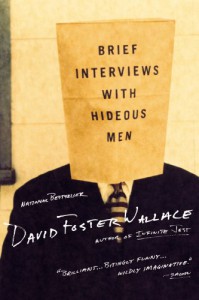

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men - Look At It

I've been treating myself to rereads of books and authors I love, and I just reached to the Wallace shelf the other day with my eyes closed, so this got read again, and only for the second complete (cover-to-cover) time since I bought it because I didn't like it loads the first time. Honestly, if it wasn't written (and signed) by David Foster Wallace, I'd have given it away - not because it's oh so awful, but because it seemed like - on that first read - an uncharacteristically unending parade of toxic masculinity, which (as it turns out, on a reread and more than one close reads of a few pieces) is precisely the point and not at all true.

My penciled notes (I use pencil first, then go to various colors on later reads) haven't all remained legible, but they are harsh. Tucked in the back of the book was an envelope with an article written by David Foster Wallace, which I just learned can still be found online, so here is DFW on Great Male Narcissists in literature.

There's much to love about that piece. Here's one of many paragraphs I have squared off w/ my pencil:

incorrigibly narcissistic, philandering, self-contemptuous, self-pitying … and deeply alone, alone the way only a solipsist can be alone. They never belong to any sort of larger unit or community or cause. Though usually family men, they never really love anybody-and, though always heterosexual to the point of satyriasis, they especially don’t love women.

What Wallace castigated in his ''Great Male Narcissists" piece - he goes after John Updike, and I'd add a hard case of Philip Roth to the mix. I'm sure there are many more, but these two men pioneered then glorified and received mounds of awards for toxic masculine self-absorption with a seriousness that doesn't seem to fit the subject matter. Women are readers these days, says Wallace, and women don't like those characters. (Complete with possibly the best quote ever, that I hope came from Mary Karr, but she won't claim it now that it's famous: "penis with a thesaurus.")

Wallace's hideous men here might be a kind of mirror held up to the characters in these most toxically male novels. Not surfacely toxic like American Psycho, but the ones that seem more benign - even sometimes just stupid. I think Wallace was staring at humanity and showed us in these stories a bit of the ugly side of what he saw.

On first glance, these characters (all written in a terrifying first person feel, even if it's not actually in first person. In other words - you feel like you're inside these hideous men while reading these stories - no, you eventually become the people, whether you want to deal with that or not) but anyway, on first glance they seem like caricatures. On a closer look they are carefully constructed and while hideous and scary, this book contains some of the best writing DFW did (and I'm including Infinite Jest in that appraisal.) After IJ, Wallace was clearly upset that everyone found his very sad and terrifying novel "hilarious." He didn't set out to write an hilarious novel and didn't feel he had. I'd agree with him that IJ isn't just hilarious, but there are parts that are very very funny, and there's no getting around that.

So Brief Interviews feels like a direct reaction to the reaction that IJ got. Nobody would call this "hysterical realism" or find much about this funny. What is so sad is that this book got horrible reviews in many quarters because it requires close attentive reading, deconstruction, doing a fair amount of research at times, certainly a dictionary and internet access if you are to understand some of these stories. He knew that. He probably knew the newspapers with their deadlines would not "get" this book, and he surely could have guessed that many people would mistake the author for any one of the horribly misogynistic, self-absorbed, overly verbal yet emotionally stilted men found in the pages. Or maybe he didn't think that far. I don't know. I honestly didn't spend much time reading criticism of DFW until after he'd died, and then it was just because I wanted more DFW and rereading everything every year only got me so far for so long.

While this is the second time I've read this in its entirety, I've read many of the pieces very closely many times. This book contains a few of my favorite pieces from David Foster Wallace: The Depressed Person, Octet, Think, Suicide as a sort of Gift (which I like more for personal than literary reasons,) Datum Centurio (which took me at least 10 reads just to begin to crack the code - but it's oh so worth it,) the prayer-like overview of life found in a young boy's dive -- Forever Overhead, and the stunning Church Not Made with Hands. Those are my favorites. That's a lot of the book right there.

And holding all of these gems together are the Brief Interviews. They have no questions because the men answering know the questions and don't need some interviewer to ask the obvious. They tie the book together - making it, in some weird way like a novel - defending against what they know we think.

This book, like all of Wallace's fiction, makes the reader sweat. If you're not educated in many subjects, like I'm not, you have to work harder to figure out what might be a reference even before you then move on to what that reference might mean. As in all of his work, it requires a dictionary on round one, note-taking and time - time and more time. It requires multiple readings, and it rewards them (much like all of his fiction does. The later the writing, the more time it will require.) Sometimes it requires reading aloud, over and over. Sometimes it requires a notebook to write questions and then another notebook to puzzle them out. And maybe a third or fourth when you find you've gone down a bad alley and need to find your way back to a better start.

"Look at it."

demands an uncharacteristically short sentence very early on. And that's really what this entire book asks of us. Look at it. Not at him - but it -- life, death, horrors, terrors, bullshit, you name it. At the end of that story, I've written (in a later read - purple pen) a long paragraph that includes "this is the whole book. He wants us to stop and really look" and after more words ends with "We need to STOP. and THINK. And allow ourselves to feel it for as long as it takes, no matter how horrible that is." So, clearly I'm not the writer, but it stuck me somewhere along the line that this was exactly what my shrink took decades to beat into my brain and still reminds me on a bi-monthly basis. It's too easy to just stay up on the surface. I need someone to remind me to plumb the depths. I think these stories, the book entirely asks the reader to do exactly that - plumb the deep, scary depths.

And yes, that's way more work than I'd offer to many writers. I can think of two (only one of whom is still alive) I have enough faith in to do the work required every time. Sometimes it doesn't pay off. I've found that with Wallace, especially as he matured as a writer, it does.

I doubt I was Wallace's intended reader. I think he thought his reader would be more literate than me and I know he expected his reader to be more formally educated than me. I have advanced degrees but they are very narrow subjects and I spent my early life in music school, so I missed a lot of that classic liberal arts education. I think he thought his readers had a lot of the references already at their fingertips. No matter. I find that reading like this is more satisfying than almost any other kind. And even so, I wouldn't recommend this book to anyone. I might suggest it if someone asked for certain things. I've suggested some of the pieces to other people, but only in response to something specific they've discussed with me.

Why am I willing to work so hard to make sure I'm getting as much out of this book, and his other work too, as I can? Because it's worth it to me. There is a pay off. In fact the payoff is bigger every time I put a bit more work into it. The feeling isn't like figuring out a problem. It's like finding a deep truth or meaning or finally grasping something you have sort of felt for a long time but never had enough of a grasp to figure out. I find meaning in this work.

And the meaning isn't "misogynistic bullshit" like some reviews I've read on some sites. It's exactly the opposite, actually. These men are, by and large, misogynists (and the women aren't so hot either.) Everyone is hideous, save perhaps the diving boy and the man in Think (though even he is not a perfect specimen.) But this hideousness is something we've all seen, perhaps been - if not exactly in the same way. There's a universal truth in this group of stories, and there's writing that I can't even begin to explain (though I'd recommend Zadie Smith's essay "The Difficult Gifts of David Foster Wallace" for a clear and understandable explanation of why this writing is so blindingly excellent at times.)

So, if on a first read I found these nameless men and women almost cartoonish, it's because I could only see the surface on that read. Here's what I wrote after that read:

These men really are hideous. I mean they are awful people, and people is a very kind word for these characters. So few of them have names or faces. They are simply babbling egos, many of them narcissistic others outright sociopaths The word hideous is important because it is exactly correct, yet so many of them come off as your average know-it-all at the bar it's depressing. Structured around the "brief interviews - given places and names, but only answers" the stories are unrelentingly bleak and horrible. I can't even call them tragic because they're not complete enough to be tragic characters.

I was wrong. They're more complete than I could see on a first read. I was looking for an easy answer, not a psychological/philosophical ocean that I'd need to dive into and swim for a while before I could understand what lies beneath.

Wallace was most experimental in his fiction, and his craft and talent are on rare display here, with none of the easy humor or zing found in all of his previous work (including his political reporting and scholarly work.) Infinite Jest is a much easier read. It feels like a beach read compared to these very short stories.

But there's something much more real here. Something that I can't explain. I learn about people - myself included - from reading these stories. He was already, in this first work after Infinite Jest, pushing himself to a much deeper place. And he set a high wire that he manages to walk in most of these pieces.

This book gets a bad rap because everyone wants it to be easy and they want it to be like the earlier nonfiction or Infinite Jest. It's not. It's different. You can feel the growth of an already talented artist here. But I can't recommend this group of stories - or any of Wallace's fiction - to anyone without knowing something about that person and what they might be seeking. The one person I've recommended most of these pieces to is my therapist. And I read them along with him, notes in hand, breaking things down, explaining what I thought various things mean. (And, um, I'm SURE I'm wrong about most of these things.) But this is the kind of person I'd recommend these stories to - someone who is deeply concerned with the darkest, saddest, hardest parts of humanity, and someone who already knows how ugly human beings can be when they're shown without any fancy make-up and easy laughs.

If it sounds like I'm defending this book, I am. I think this is Wallace upping his game, projecting toward what he might try to do in long form in a novel someday. I don't know if it's doable in long form. It could be way too hard and way too heavy. This book is very heavy, but once I started to break it down, and really read it carefully, I became even more enamored with the soul of David Foster Wallace, and to me that soul is anything but hideous.

2

2